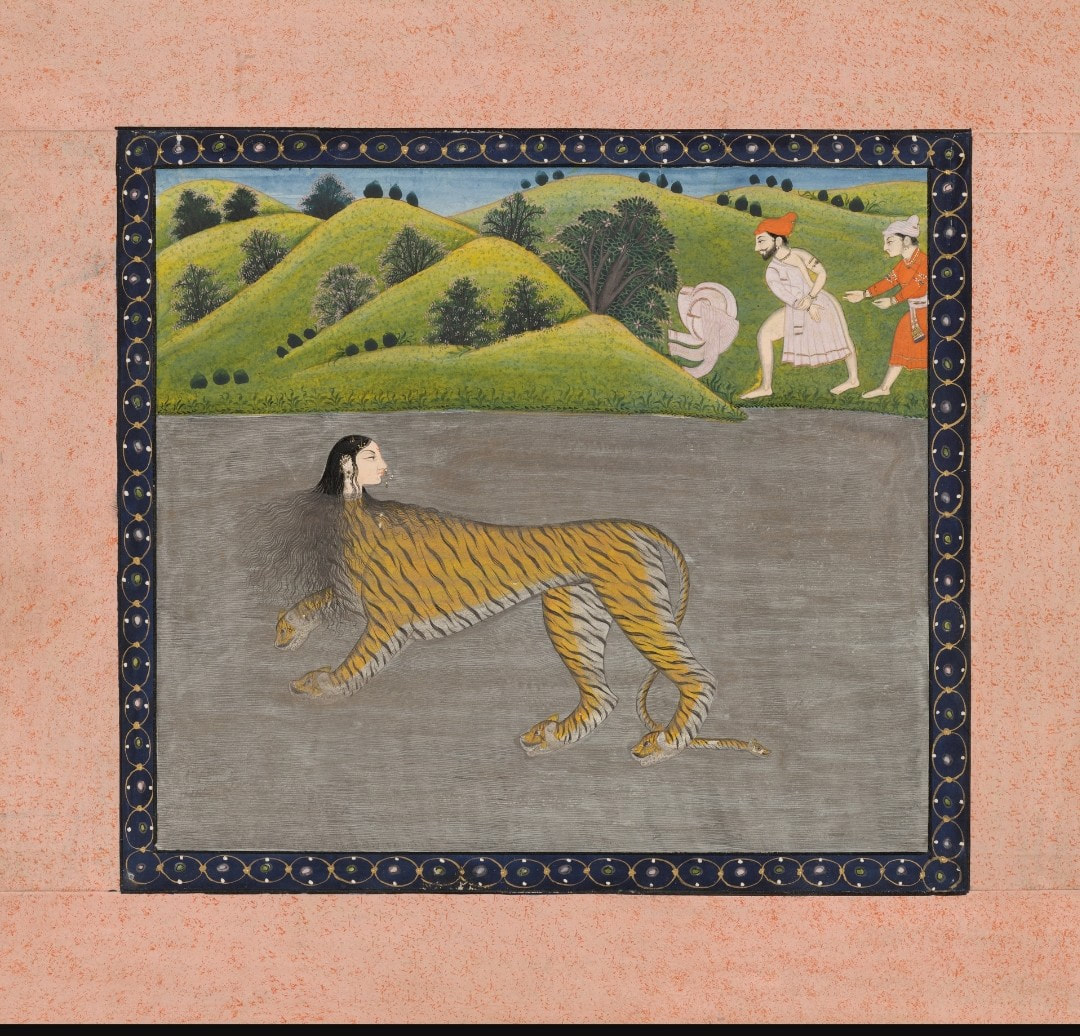

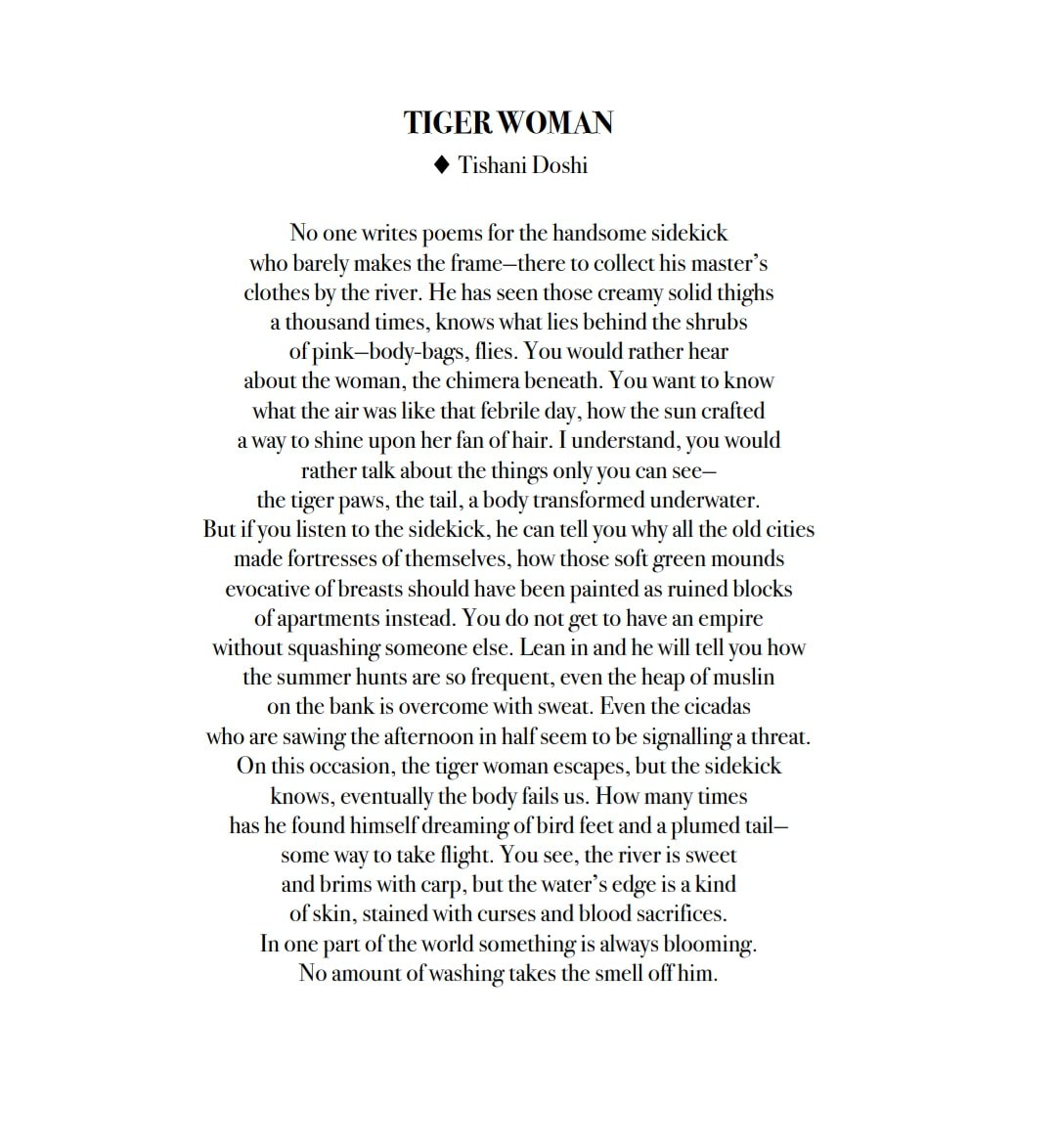

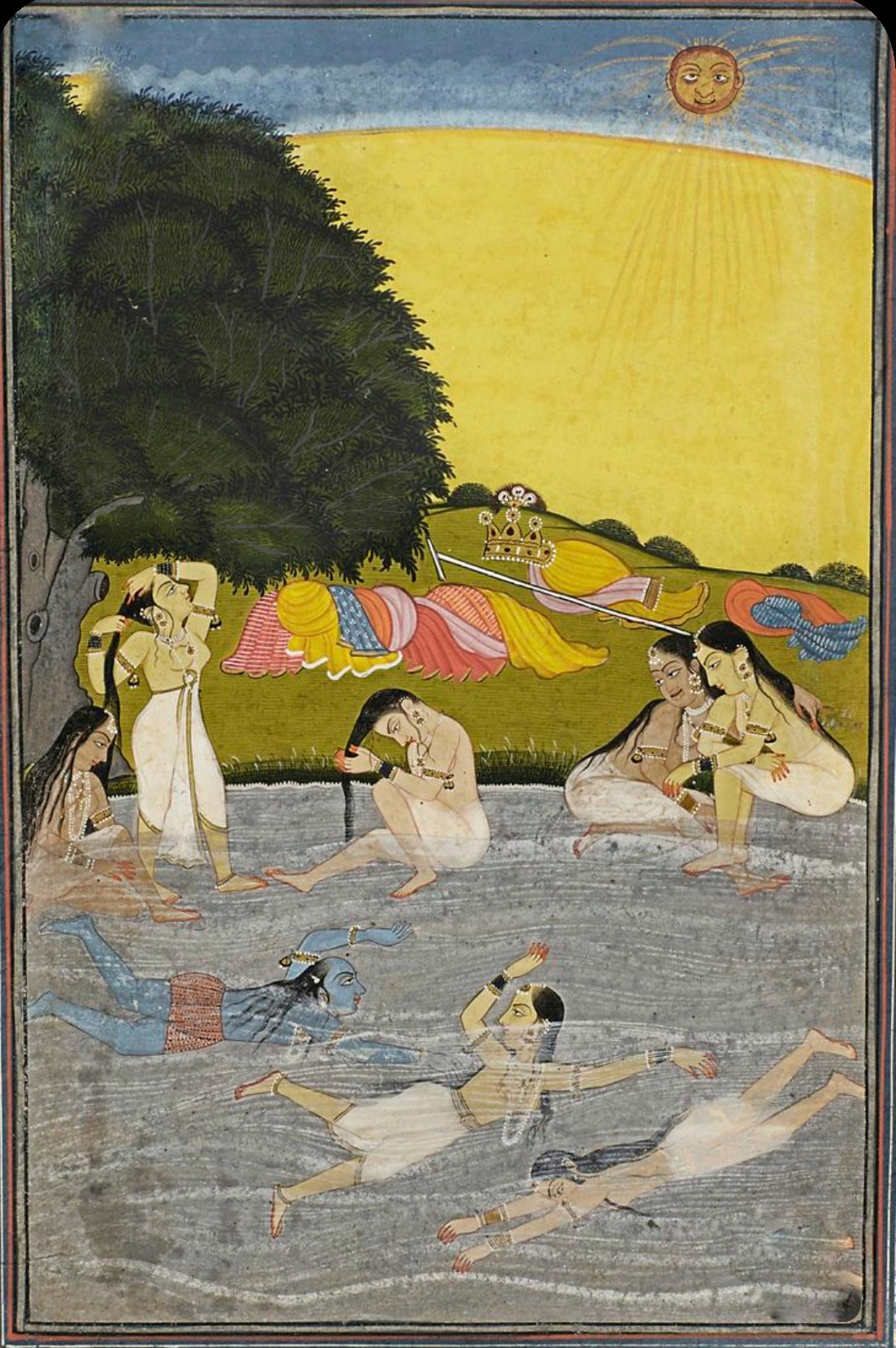

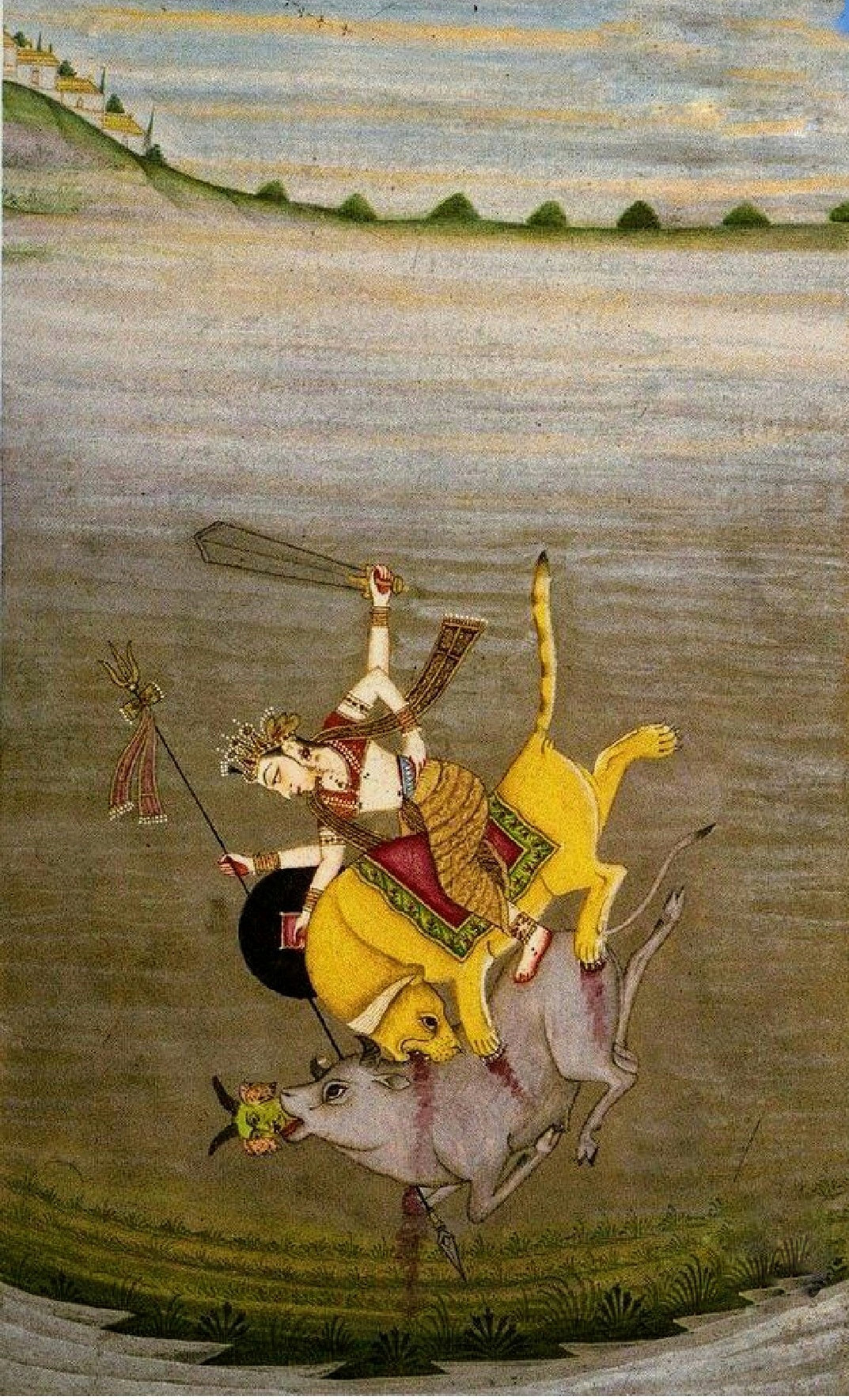

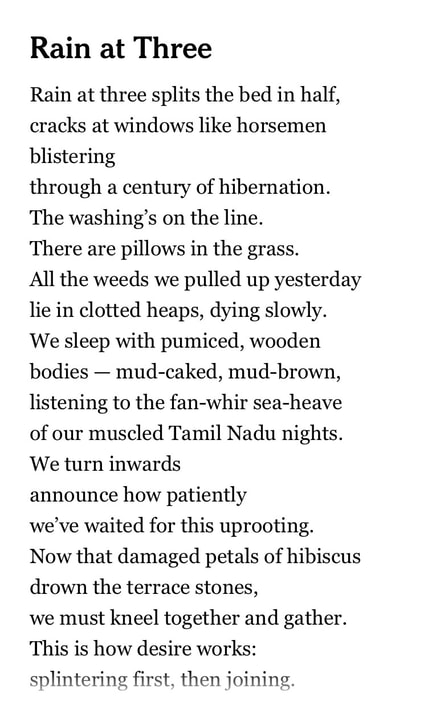

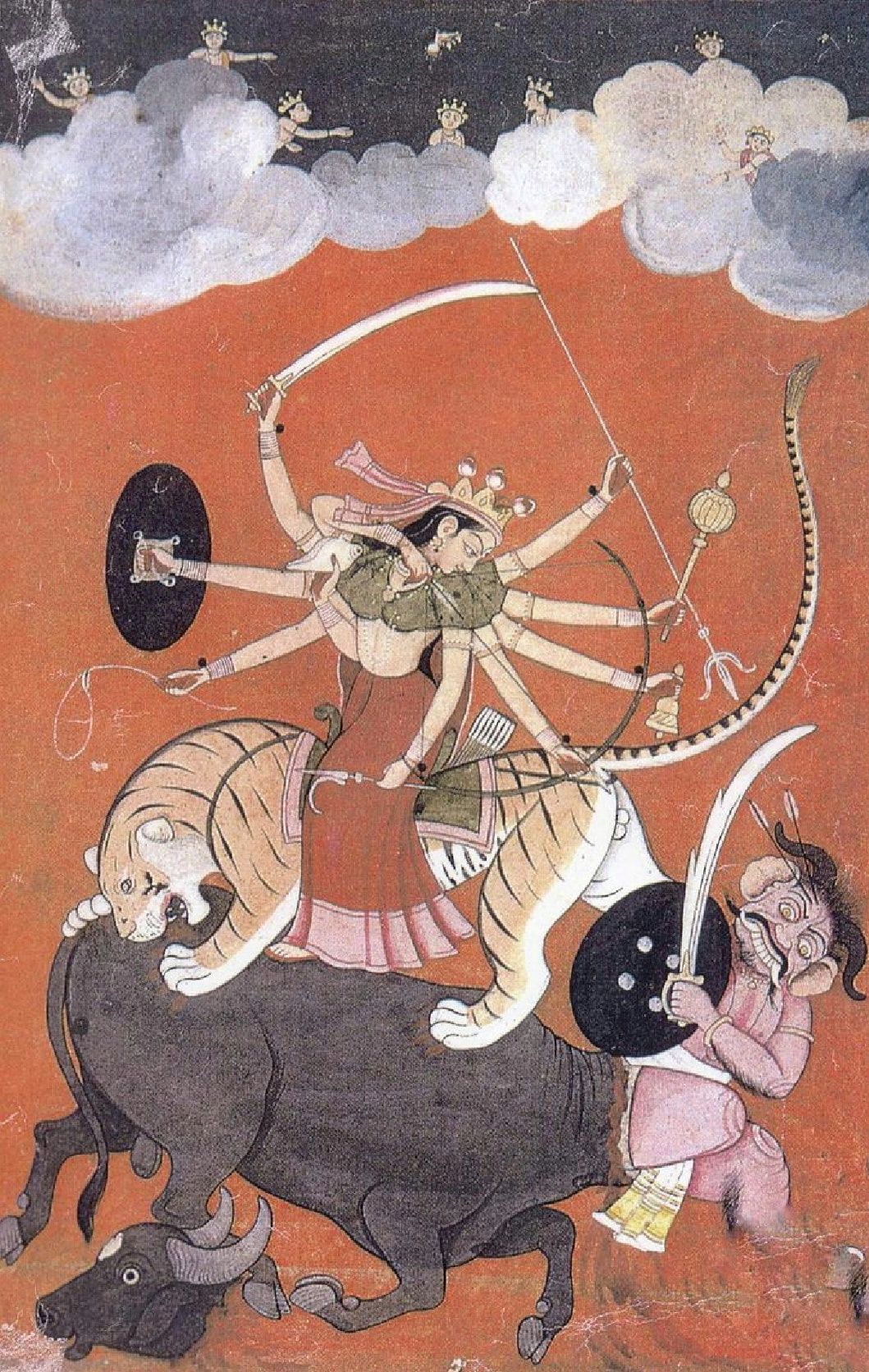

New poem published in the Royal Academy of Arts Magazine / Responding to a 19th Century Mughal Watercolour - "Tiger Woman"

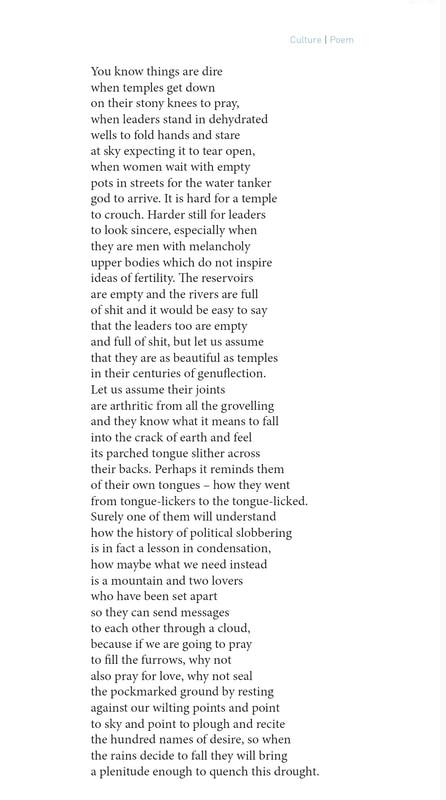

A New Poem in the Autumn 2019 Issue of New Humanist: Everyone Has a Wilting Point

"RAIN AT THREE" IS FEATURED IN THE NEW YORK TIMES MAGAZINE

|

|

HOW TO WRITE A POEM

Steal a first line if you must. After you’ve finished writing the poem, destroy that line. Or not. Newspapers can be a good source of inspiration. Or not. Handwrite, preferably in turquoise ink. Or not. Worship words and keep a notebook filled with them. Or not. Memorize a poem you love. Or not. Understand that poetry is held in the body—that it works to a different kind of time and rhythm from prose words and news words and figure out how to inhabit that time. Or not. Long walks may help. Or not. Listen to Baudelaire: “Be drunk” —on wine or virtue, but be drunk. Or not. Proceed. Or not. |

Sunrise at Sanchi Stupa

We were sitting outside the stupa that morning when the sun shone

down like a woman sweeping clear roads of dust

and dreams making me wonder if love can find its way like this

through broken valleys past shattered edge of bramble thorn

and bruised foundation of of monastery

all-conquering love doesn't stir in the dark to talk to guards

doesn't have the quietness of cows doesn't run with incense rage

across the bougainvillea fringe of the world

If love were really born of fire we'd build giant domes of sky

around our gossiping pasts and silence them

with bits of tooth or graft of hoary nail we'd let the roads consume

our steps our columns of desire

and when morning broke the scattering earth with blood red

points of light all the distances of night

would brush us by as the undergrowth of our unfinished lives

From Countries of the Body

We were sitting outside the stupa that morning when the sun shone

down like a woman sweeping clear roads of dust

and dreams making me wonder if love can find its way like this

through broken valleys past shattered edge of bramble thorn

and bruised foundation of of monastery

all-conquering love doesn't stir in the dark to talk to guards

doesn't have the quietness of cows doesn't run with incense rage

across the bougainvillea fringe of the world

If love were really born of fire we'd build giant domes of sky

around our gossiping pasts and silence them

with bits of tooth or graft of hoary nail we'd let the roads consume

our steps our columns of desire

and when morning broke the scattering earth with blood red

points of light all the distances of night

would brush us by as the undergrowth of our unfinished lives

From Countries of the Body

"THE DELIVERER" by Tishani Doshi, featured in Poems of the Decade

I've been receiving lots of emails about this poem, so thought I'd put some notes here for reference.

The mother is the deliverer, a kind of stork, if you will. She brings the baby from the convent in Kerala to parents in the U.S.A. She has journeyed with the child, so she feels emotionally tied to it. She’s a mother herself, so she knows what it means for this child to be taken into this family.

The video tapes refer to actual video tapes (obviously, we’re talking about an earlier technological era), when parents made home videos of their children. The poet supposes that the American family will take photographs and videos of their adopted baby girl. They will chart her progress. And then there is a jump in the poem, we view things through the girl, maybe when she's grown up, and she looks at these videos of herself when she's growing up, she might wonder about where she began. Is there that knowledge in the body that allows for this kind of memory? Will she know that she was abandoned, half buried in the ground, left for dead, will she be able to imagine her beginnings?

This is, I suppose, the crux of the poem. The male child is still preferred over the girl child in India. Female foeticide and infanticide are still widely prevalent, so much so that it is illegal in India for a clinic or doctor to tell parents about the sex of their baby during the pregnancy. Many Indian women don't have access to birth control and therefore have little control over their reproductive rights, which takes us to the final image of the poem - the women trudging home to lie down for their men again.

This poem was written from an actual experience. My mother did take a baby to America. She told me some of the stories that the sisters at the convent told her - how rare it is for people to give away their boys, that in India it is mainly girls who are abandoned. I tried to imagine the life of this particular girl she delivered. I thought as well about my mother's own journey from North Wales to India. This is a poem about memory and the body, about where we begin and where we end up.

I've been receiving lots of emails about this poem, so thought I'd put some notes here for reference.

The mother is the deliverer, a kind of stork, if you will. She brings the baby from the convent in Kerala to parents in the U.S.A. She has journeyed with the child, so she feels emotionally tied to it. She’s a mother herself, so she knows what it means for this child to be taken into this family.

The video tapes refer to actual video tapes (obviously, we’re talking about an earlier technological era), when parents made home videos of their children. The poet supposes that the American family will take photographs and videos of their adopted baby girl. They will chart her progress. And then there is a jump in the poem, we view things through the girl, maybe when she's grown up, and she looks at these videos of herself when she's growing up, she might wonder about where she began. Is there that knowledge in the body that allows for this kind of memory? Will she know that she was abandoned, half buried in the ground, left for dead, will she be able to imagine her beginnings?

This is, I suppose, the crux of the poem. The male child is still preferred over the girl child in India. Female foeticide and infanticide are still widely prevalent, so much so that it is illegal in India for a clinic or doctor to tell parents about the sex of their baby during the pregnancy. Many Indian women don't have access to birth control and therefore have little control over their reproductive rights, which takes us to the final image of the poem - the women trudging home to lie down for their men again.

This poem was written from an actual experience. My mother did take a baby to America. She told me some of the stories that the sisters at the convent told her - how rare it is for people to give away their boys, that in India it is mainly girls who are abandoned. I tried to imagine the life of this particular girl she delivered. I thought as well about my mother's own journey from North Wales to India. This is a poem about memory and the body, about where we begin and where we end up.

THE DAY WE WENT TO THE SEA

The day we went to the sea

mothers in Madras were mining

the Marina for missing children.

Thatch flew in the sky, prisoners

ran free, houses danced like danger

in the wind. I saw a woman hold

the tattered edge of the world

in her hand, look past the temple

which was still standing, as she was -

miraculously whole in the debris of gaudy

South Indian sun. When she moved

her other hand across her brow,

in a single arcing sweep of grace,

it was as if she alone could alter things,

bring us to the wordless safety of our beds.

from COUNTRIES OF THE BODY